There have been many millions of words penned about the technical limitations of the microgroove record over the years. Here are some more… a lot more, as it turns out. Again, this is all my perspective and gained from recent experience. If you just want some basic dos and don’ts without all the waffle, head to the bottom of the page.

Does vinyl sound better or worse than CD or digital?

Right, straight off and we’ve hit a problem. “Better” is almost a meaningless term when talking about audio. Everyone’s tastes are different, everyone’s hearing is different, everyone’s equipment is different. You can get into facts, figures, talk of dBs and frequency ranges and cm/s and bit-rates and ‘warmer’ and heaven knows what else, but sound is ultimately subjective.

What vinyl won’t do is give you an exact duplicate of a digital audio source. It often won’t give you an exact duplicate of an analogue audio source, either. Sticking a sharp point into a moving groove and getting sound out of it goes right back to Edison and his wax covered cylinders. The basic idea was refined and improved and changed massively during the following century… cylinders to shellac discs, big acoustic horns to microphones and amplifiers, shellac discs to polyvinyl chloride, 78 to 33 and 45rpm, mono to stereo, quadraphonic, half speed mastering etc. But you’re still sticking a sharp point in a moving groove, like Thomas did when he listened back to himself reciting Mary Had A Little Lamb for the first time in 1877.

So what does this all mean? Why will my music sound different?

Various reasons!

The first thing is to note is that you can’t get the same sort of top end out of vinyl as you can with a digital source. You can cut those frequencies into the disc to some extent (or some people can, more on this shortly), but you can’t always get them back again. Obviously the higher the frequencies, the faster the cutting stylus has to move to create that pattern in the groove. Then when it comes to playing it back, the stylus on your record player has to try and follow that groove, which is a lot more difficult. When it can’t follow the groove correctly, you get nasty distortion. A lot of this is due to people’s playback equipment, cheap record players (and badly set up expensive ones) just can’t ‘track’ really high frequencies properly. You then might get into a world of protractors and anti-skating weights and hyper-elliptical styli and cork mats and snake-oil cables in search of the ‘perfect’ sound, which might never have been there in the first place. Just take it as read that a lot of people are going to be playing records on a horrid plastic thing that cost them £30 from a supermarket.

In fact, there’s some distortion everywhere in a vinyl groove. But it’s not always unpleasant… think of a square waveform from a synthesizer oscillator. It’s physically impossible to cut an actual square waveform into a groove, the cutting stylus just can’t move that quickly from side to side, and even if you could cut it you’d never be able to play it back. So the sharp edges of that waveform get ’rounded off’ to some extent. Some people might call that ‘harmonic distortion’. Some people might call it ‘warmer’…

So no matter what you do (unless you were cutting a pure sine waveform, which could be a bit dull to listen to) the audio gets changed in some way or other. There’s just no way of getting around it. We’ve been spoiled with digital sound somewhat over the recent past. You put in a square wave, that’s exactly what you get out. Now, you’ll get some going on about sample rates, 44.1khz isn’t enough, you get steps in your waveforms, it sounds harsh and all that. This is where personal opinions get in the way of any science, and it’s a bear pit I’m not jumping into. Suffice to say, records can sound really great, and they’re nice things to have. Heaven knows, I’ve got thousands of the things here… And you must fancy having your sounds on a record rather than a CD or digital file, or you wouldn’t be reading this. Right? Right…

Back to the top end for a moment, if I may… To get as much information into a microgroove as possible, a standard was agreed a long time ago for EQing the signal… the low end gets cut back and the top end gets hugely boosted. This allows the groove to take up much less space. When the record is played back, the EQing is reversed in the phono stage so you get more or less the original signal out again. So when cutting a disc, a large amount of power is put through the coils of the head, and the more top end there is to start with, the more excessive the current gets. The coils in the head get hotter, and there’s a danger of burning them out, just like you might do with a speaker (which is what my cutter head basically is).

As cutter head design progressed during the 1960s and 1970s, manufacturing techniques improved, systems were designed to stop the coils from overheating, and this resulted in the heads being cooled using water or helium. Eventually we arrived at things like the Neumann SX74, which could (and can) cut extremely loud discs with frequencies pushing 20,000hz. All well and good. Unfortunately, the last one of those was made in the early 1980s. Finding one now is near impossible, and they cost an actual fortune when they do show up, it needs corresponding electronics to work properly, and it wouldn’t fit on my lathe anyway… plus I don’t fancy having helium cylinders knocking around the house.

My little T560 setup’s cutting head is more akin to a 1950s design, and it quite basic. It doesn’t have a feedback system (which essentially allows a flatter frequency response) and there’s a limit as to how far I can push the treble before things get distorted and nasty, or indeed before something goes pop. The head does have protection fuses, but I can’t take the risk that a fuse might not act quickly enough and let a spike through that might blow a coil up (which would cost me hundreds to pounds to have fixed). So, if you send me something with a lot of bright and airy top end on it, please be aware that there’s a good chance it won’t come back like that. I’ve only had a couple of instances where this has been an issue, but just so’s ya know. Also see the section on de-essing, below. The lower the overall cutting level, the more I can accommodate the top end, but as with everything in this game it’s about trying to find a happy medium.

So what are the other limitations?

Many and varied.

I’ll try and cover the basics in as short a time as possible, as I’m in danger of boring myself here. When cutting something to a vinyl disc, there are three underlying factors that you have to take into account:

- The length of the material

- The amount of bass present

- The overall volume of the disc

Here we have a classic case of ‘pick two’. The length of the material will determine how much of the physical space on a blank record that the groove takes up, no matter what speed it rotates at. Bass frequencies require the groove to move more from side to side than higher frequencies. To cut the material ‘louder’, everything is magnified. When you magnify everything, the room needed for those bass frequencies grows more than anything else, and that reduces the amount of time you can have that wide groove spacing going on before you run out of space on the disc at the middle.

So, imagine we’re trying to make a 7″ single. If you want it really loud, and it’s got lots of bass in it, then that limits the time the music can play for. If you want it to play longer and have lots of bass in it, then that limits the volume that the record can be cut at. If you want to get something quite long onto that 7″ and have it loud, then you need to cut the bass back.

Is that it? Bass vs volume vs running time, then?

Oh, dear me no. There’s lots more to it. Remember me going on about high frequencies before? Well, there’s more on those, for starters. But first, a cartoon… (apologies to Bill Watterson)

Yeah, I still lie awake occasionally like that. However it’s totally relevant. At the outside of a disc, the surface moves faster beneath the stylus than it does when you get nearer to the middle. What that means in practice is that there is less and less space to fit all the information in the longer the disc plays for. Think of it as bandwidth… When you try and pack loads of information (especially treble) into that slower moving groove, distortion levels go through the roof because the cutting stylus gets to a point where it’s almost making right angles into the plastic. If you’ve decided that you want that 7″ single we were talking about to rotate at 33rpm rather than 45, so you could get more onto it, the problem gets even worse.

Basically, the faster the disc rotates, and the further out from the middle the groove is, the better it’ll sound. So if you had a nice bright track which lasts about 6 minutes, it’d be better to cut it into a 10″ disc at 45rpm than try and pack it onto a 7″ at 33… It’ll sound so much better.

There’s also another thing to consider, which is ‘tracking error’. Yes, I know we’re getting really technical now, but I’m on a roll. Not only is the audio information somewhat squashed at the end of a side, the angle at which the stylus tracks the groove on a normal record player (i.e. one with a swingy arm rather than a fancy linear tracking system) is less than optimal. In hi-fi circles, much is made of setting up the cartridge and stylus to minimise this ‘tracking error’ and the resulting distortion as much as possible at both ends of a side.

I have to admit that only recently, after 40+ years of playing records, have I finally sorted out a turntable with a properly set-up cartridge and fitted with a nice stylus. £150’s worth of Audio Technica VM95ML, before you ask, none of that insanely expensive audiophile stuff. The difference is really like night and day. LPs which descended into a distorted mush on those last couple of songs on all my old equipment often now sound damn near perfect. But only a small percentage of people with ‘record players’ are ever going to go to those lengths, and even those Concorde type cartridges fitted to so many people’s SL1200s really undersell the format. This is why CD was such a success, just stick one into any functioning player and it sounds absolutely fine. Pfft. Am I rambling now? Probably.

So how much can I get on a disc, then?

Well, as you can hopefully see, it varies greatly depending on the size of the disc, the speed it rotates at and the length/content of the audio. To play safe, here are some rough guides on sensible playing times, assuming the cut is to be at a decent (rather than very loud) volume and the low end is kept mostly intact.

- 7″ at 45rpm – 3 to 4 minutes

- 7″ at 33rpm – 4 to 6 minutes

- 10″ at 45rpm – 5 to 9 minutes

- 10″ at 33rpm – 9 to 12 minutes

- 12″ at 45rpm – 7 to 10 minutes

- 12″ at 33rpm – 15 to 18 minutes

As I say, this is only a really rough guide. Certain material might allow for longer playing times, other material might have to be less. For example, I can (and often do) get 5 minutes onto a 7″ at 45rpm, but it’ll be quieter, you won’t have any floor shaking bass in it, and there won’t be a lot of room to scratch a witty message into the run-out groove area, which I’m sure you’ll agree is the most important thing… the world of records would be a much duller place without George ‘Porky’ Peckham’s little inscriptions, eh?

I’ve got records that last longer than that…

Undoubtedly. However, one major factor in that will be that most pro-cut and pressed records were originally cut on a lathe with a pitch computer. What that means is that the lathe had a system where it was fed a copy of the audio signal before the signal actually went to the cutting head/stylus. It could then adjust the distance between the grooves (yes, it’s one groove but you know what I mean) depending on the volume/bass content of the signal. So if there was a section of really quiet music, it could pack those grooves (yes) closer together, then when it sensed that things were kicking off in a revolution’s time, it could open things up again. Most records from the mid 1970s onwards were cut with this technology. Compare (for example) an original 1969 pressing of Abbey Road with one from 10 years later, and you’ll see that the groove on side 2 gets very close to the middle indeed, whilst later copies with a recut lacquer have significantly more ‘dead wax’.

Anyway, my lathe doesn’t do that. Yet (he says). So for the moment, I have to pick an appropriate pitch/spacing to accommodate the loud bits, and stick with it for the duration of the track/side, or sit there twiddling the pitch knob as the thing cuts to try and save a little space. I’ve managed to cut a 25 minute LP side at a very conservative volume successfully, but it was a bloody nightmare.

I’ve seen other modern day ‘lathe cutters’ do an LP side literally right up to the label, and some even offering smaller labels to ‘get more music on’. Well, yeah you’ll be getting more music on I suppose, in fact you could theoretically cut a groove right up to the hole in the middle, but it’ll sound absolutely dreadful due to the ‘lower bandwidth’ and increased tracking errors I mentioned earlier, so what’s the point?

Also, some of the horrible cheapo record players that people have these days have an ‘auto stop’ thing, which basically means the motor gets cut off at the end of a side. Or to be more accurate, *near* the end of a side. The result is that if I cut something past the standard point where the inner lock groove on a 12″ disc would be, there’s a good chance that the thing will just stop playing. The lock diameter on a 7″ is actually smaller, and many commercial discs from the ’60s onwards have been cut very close to that indeed, so there’s a good chance that they don’t play properly on those crappy players either, but I don’t have one to check the theory. Anyway, best not risk it, eh?

But I need my records to sound really loud!

Do you really? Are you sure about that? I’ve mentioned ‘the loudness wars’ elsewhere on this site, but it’s worth perhaps having another rant about it here. This all goes back to the 1950s and 1960s, when the two main outlets for rock and roll were radio stations and jukeboxes. That’s when radio stations really started employing compressors and limiters to make their signal appear to be louder than the competition, so when Bobby and Angie were out cruising the strip in their dad’s Oldmobile (or in the UK, driving around the town centre in mum’s Morris 1000) and they twiddled the AM radio dial, they’d stop on the station that jumped out of the speakers.

Likewise when down at the cafe, pumping coins into the jukebox. The amp volume on those was always pre-set by the owner, so the punters couldn’t mess around with it. So, cutting a record ‘louder’ would mean that there was more chance of it being heard above the chatter, coffee machines, clinking of coke bottles and the sounds of fighting. This also meant that these records would absolutely blast out of the little portable record players that were commonplace at parties in the ’60s and ’70s, despite their amps only putting out a couple of watts at best.

Anyway, that’s continued to this day. Setting aside the squashed dynamic range of most digital recordings these days, there’s a desire to still have vinyl records cut at the loudest volume possible. Now there is the factor of signal to noise ratio to consider, i.e. you want the music to be heard above the surface noise that is an inherent part of the vinyl format (no matter how or where it’s cut). But once you get past that, you don’t need everything to be cut at +9db slamming into the red all the bloody time. Amplifiers have volume controls. DJ mixers have gain knobs.

The louder you cut a record, the more distorted it will sound overall (and the more strain it puts on my equipment), the more problems there will be with sibilance (see below), the more compromises you have to make with frequency range, and the less time you have to play with. I’d much rather you had to turn the amp up a bit than make a record that sounded loud but crap.

Okay, okay, calm down… What about all this stuff about bass having to be mono?

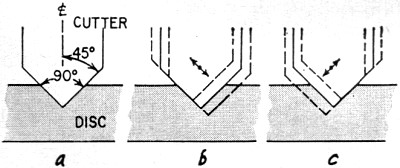

Indeed, and there’s a good reason for it. To get to the bottom of the matter, hopefully not getting too technical about it, and ignoring tons of history, a mono groove just moves from side to side (laterally), and thus does the playback stylus. When the first stereo discs were introduced in 1958, they’d adopted a system known as the Westrex 45/45… so called because there are two drive coils, mounted at 45 degrees to the disc.

In this system, the groove not only has lateral movement (side to side), but also vertical movement (it gets deeper and shallower). But it’s not that one plane carries the left channel, and one the right. The mono part of a stereo audio signal, i.e. the stuff that’s dead centre in the stereo picture, is cut into the lateral plane of the groove. The stuff that’s panned to one side or the other gets cut into the vertical plane, and it’s cut ‘out of phase’. Mid/side for those who know. I’m starting to wish I’d never started typing this.

To cut things a bit shorter, when you’ve got low bass content panned over to one channel or the other, you end up with large modulations in the vertical plane. Effectively the groove becomes a very tricky rollercoaster for the playback stylus. If you then start adding stereo effects to that bass content, echos or stereo-widening gizmos etc, the problem gets even worse and the playback stylus literally ends up being thrown off the rollercoaster and out of the groove. In fact, if I tried to cut that sort of thing, it could even end up with the cutting stylus trying to move in two directions at once, which isn’t good for anybody… least of all me, they’re bloody expensive things to replace.

Upshot: the low end absolutely has to be in mono, so it gets cut into the lateral plane of the groove. There isn’t a hard and fast crossover point, but for safety I’d recommend keeping everything under 170hz dead central. The more alert amongst you may have just made the connection between this and the need for more space on the disc when there’s lots of bass… it’s all connected. Circle of life etc.

Oh, and just to finish the section on bass, try and get rid of everything below about 40Hz. It takes up loads of space, muddies the sound and again you could easily end up with severe tracking problems.

So, bass in mono, keep the top end under control, stay away from the middle, no sudden movements, don’t walk on the cracks in the pavement… anything else?

Yes. Dynamics.

You need to keep your audio nice and open. By which I mean, don’t shove it through a brickwall limiting plug-in thing in an attempt to make it ‘louder’. We all know about the loudness wars over the last 20 years or so, arguably started in earnest when digital tools like Waves’ L1 started turning up. Again, trying to translate hyper-squashed audio into the physical movement of a tiny cutting stylus just won’t go well. The results will sound awful – distorted, muddy, tiring – trust me.

That’s not to say you can’t use compression. Far from it. Where would rock and roll be without compression? I love it, when it’s used right. Also you need to compress things to a certain extent because of surface noise. Yeah, I know… “life has surface noise” as John Peel said. But it’s always there, and despite the fact that I consider my discs to have unobtrusive levels of noise*, it is yet another problem to be overcome. Vinyl doesn’t have the usable dynamic range that digital files / CDs do.

So don’t squash the life out of your music, leave some headroom there (-6db would be a good amount), make sure there’s no digital clipping going on. Make it pump and breathe by all means, make it loud, but don’t turn it into a hard-limited sausage. You won’t like the results, and neither will I.

* Again, subjective! But I’ve heard enough records in my life to know what I personally consider acceptable and not acceptable. I’ll upload some comparison files when I get the chance. Actually, talking of surface noise…

Can we talk about surface noise? I’ve read that lathe cuts have more than pressed records.

Okay. It might be worth tackling what actually causes surface noise on a record. Obviously, scratches and dust and stuff cause pops and clicks, but there is always inherently some unwanted general noise on a stereophonic gramophone record. On a pressed record, it’s caused by microscopic imperfections in the surface of the disc and within the groove, which are picked up by the stylus. These imperfections are quite simply down to the quality of the raw PVC used to make the disc, and the care taken over the pressing process. If low grade PVC pellets are used, and/or the discs aren’t put in the presses for long enough and allowed to heat/cool properly (which happens a lot now, due to the over-production at pressing plants) you end up with a rougher surface to the disc – sometimes this is actually visible – and more noise.

Aside: The fact that this roughness to the surface is in the vertical plane of the styluses movement means that the unwanted noise is generally out of phase (see a couple of paragraphs up), and that’s why hi-fi amps used to have a ‘mono’ button on them. Mono records don’t contain any information in the vertical plane, so pushing that button in inverts the phase of one channel, which has the effect of leaving the mono signal intact but cancelling out the majority of unwanted noise. Magic!

So, surface noise on lathe cuts. On a traditional lacquer, it’s possible to cut a virtually perfect, silent groove as the material is so soft. When cutting into solid plastic (PET-G in this case) it’s not quite so perfect, despite heating the disc and stylus to aid the process. Generally, we’re talking levels of noise comparable or less than the majority of pressed discs when everything’s right. However there’s a problem in that the blank discs that everyone uses are hardly ever absolutely flat. Any warpage of the disc, however small, means that the stylus digs in fractionally deeper as it encounters the change in surface height, and that leads to more… yes… unwanted, out of phase noise. Although I’m as picky as I can be when selecting which blank discs to use without bankrupting myself*, an absolutely 100% flat one is incredibly rare, so I can’t guarantee that every disc will be absolutely perfect. But again, if you want perfection, then CD-R might be the way to go after all!

*(I’m rejecting at least one in five at the moment, and in one dismal case a whole batch of 100 went in the bin… No, I can’t get refunds on them. But I care about what I make, you see. Possibly too much.)

Good grief. Right. Moving on, I’ve read that I should de-ess vocals?

Oh, hell yes. You should. As much as you can. And not just vocals. Sibilance is a major cause of distortion on records, and it’s not always where you think it might be in the frequency spectrum i.e. way up at the top end. You can get problems much lower down, and it’s not so much the frequencies but the rapid *change* in frequencies, and distortion on playback is due to the stylus just not being able to keep up.

It’s not just ‘sss’ and ‘ch’ vocal sounds either, as the likes of hi-hats and cymbals (both acoustic and from drum machines) can cause problems if they’re too bright and loud. And tambourines. Oh, most certainly tambourines. Really listen out for that sort of thing when you’re mixing/mastering. If those sounds ‘stand out’ when listening to your source, chances are they’ll distort badly on disc.

The last thing you want is me having to smother the whole final mix with de-essing and drastic EQ-cuts because it’s too bright to cut successfully, so try and take care of that beforehand. Mix bright vocals down, or they’ll end up all lispy. A big loud S-peak between 6-9khz can easily pop the fuses on the cutting head, which will nark me right off, I can tell you. I’ve only got so many spares.

Well, if you know everything, can you master my track for me?

No, I’m really not a mastering engineer… I’m just outlining the things which I know will cause problems at my end. I don’t even master my own records most of the time. Funnily enough, in the old days the person who cut a lacquer disc was called ‘the mastering engineer’, and was responsible for the final sound of a record – hence the myriad of different sounding pressings – but things have changed. People generally don’t want their music to sound different to their final mix these days.

I’d really recommend getting a true pro to do the job, preferably one who has actually properly mastered for vinyl before and knows the pitfalls. Again, no excessive top end, no out of phase low end, rounded midrange sibilants and no clipped waveforms. The better the source you send me, the better I can make the results and the closer to what you’re already happy with.

I have another question…

Drop me an email. I think I’ve typed enough above for the moment, but if I can think of any more important factors, I’ll put them up here in due course.

So, that was a lot of reading, but I’ll try and boil down the above to a set of points as to what is essential and what is preferable in a file that you send me.

- Format: For digital files, ideally 44.1khz, 16 bit (CD quality) or better, in .wav or FLAC format. I can cut from mp3, but 192k at an absolute minimum, preferably 320k, as long as your ears are happy with the sound of it.

- Bass: Keep anything under 150hz dead central/mono, a higher crossover would be nice if possible. Please don’t use stereo expanders/stereo phase effects on the low end, or it’ll be impossible to cut successfully (and you may even end up with the signal vanishing if I have to try and collapse it into mono). Filter out anything under 30hz, it’ll just end up as mud.

- Upper mids: Pay attention to vocal sibilants, hi-hats, cymbals and other similar sounds in the 6-10khz range. If they stand out in a mix, you can bet they’re likely to cause distortion in a groove. De-ess these tracks as much as possible during mixing if possible, if not then be prepared for some after effects to the track if I have to process things at my end. I’d say this is the most important factor in creating a disc which sounds good.

- Top end: Keep the +10khz area controlled, excessive ‘air’ and similar may cause problems. It’s best to roll off the top around 15-16khz, as above this things are unlikely to end up on the disc with any real volume anyway.

- Compression/limiting: Compression and limiting is fine as long as there’s enough headroom to cater for it in the master, although don’t go too mad with it. However, ‘hard’ limiting is an absolute no-no, as any clipping of the waveform peaks will cause major problems. Ideally send something with around +6db of headroom (and that doesn’t mean a heavily clipped/brickwalled track that’s just volume reduced by -6db).

- Time constraints: Try not to push side lengths. I’d recommend 4:30 maximum for a 7″ at 45rpm, 8 minutes for a 10″ at 45rpm, 12 minutes for a 10″ at 33rpm, 12 minutes for a 12″ at 45rpm and 18 minutes for a 12″ at 33rpm! Going over this will compromise the final product in some way(s) to some extent(s).

Paying attention to these points should give me something I can work with, without having to spend hours fiddling around and doing test cut after test cut.